Ceramicx – Using Technology Transfer for New Product Development

“Licensing new technology has enabled Ceramicx to develop cutting-edge innovation that will power the company’s latest wave of international growth.”

The Aston Martin BD9 touring car contains aluminium panels alongside fibre-reinforced plastic panels that are bound together with super-strength adhesive, developed by Irish company Ceramicx through an infrared heating process.

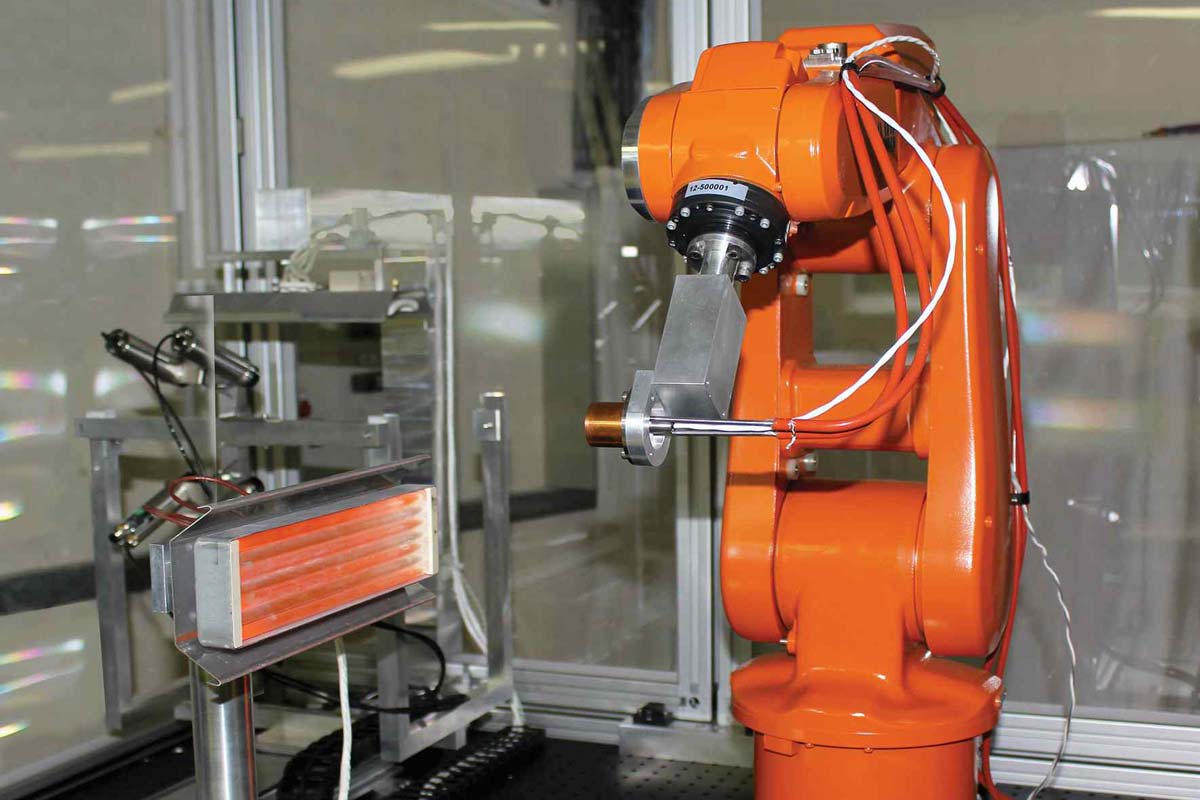

The West Cork-based company is now announcing a world-first in launching the Herschel, a machine that measures and maps infrared heating.

“Infrared is invisible, of course, so it’s a hard thing to quantify. Usually people measure infrared output as the heat produced as a secondary reaction, but the Herschel maps the output of an emitter in watts [power] per cm2,” explains Cathal Wilson, director at Ceramicx.

The technology, first pioneered at Trinity College Dublin’s Manufacturing Research Facility, is named after William Herschel, the German-born astronomer who moved to Britain in the eighteenth century and became famous for his large telescopes. He also discovered infrared radiation and the planet Uranus.

The licensing deal with Ceramicx and subsequent process of technology transfer was the fruit of an Innovation Partnership, part funded by Enterprise Ireland. In turn, it has unleashed a new avenue for international sales for the West Cork company.

The licensing deal with Ceramicx and subsequent process of technology transfer was the fruit of an Innovation Partnership, part funded by Enterprise Ireland. In turn, it has unleashed a new avenue for international sales for the West Cork company.

Ceramicx is up-skilling its staff of 63 and preparing to double its floor space, adding further labs, offices and manufacturing capacity. The Ballydehob firm is no newbie, though. The company has been perfecting its infrared heat work for 25 years, and it exports to 65 countries, with key markets being China, Germany, UK and the US.

Ceramicx will use the breakthrough technology to further refine the infrared heaters and ovens it develops in-house for food and other manufacturers. But the company also expects demand for Herschel as a test instrument for large companies that rely on infrared energy in manufacturing.

Like baking a cake, there is a heat recipe in every material, and there are a number of variables that must be controlled to get the best, most efficient and most cost-effective solution. The Herschel will allow manufacturers to refine the dial on their heat recipe with amazing precision.

“There are probably five or six major companies in the world that would be interested in this new technology,” Wilson says. These include the likes of Corning Glass, European Aerospace, Boeing and leading-edge tech companies serving likes of NASA.

The company came to realise the need for a machine like Herschel after it had worked through a challenging assignment developing a finished oven for Corning Inc., the makers of the Gorilla Glass used in mobile devices such as the Apple and Samsung smartphones. A curved piece of glass 0.7mm-thick was required, and the initial calculation and trial stages of the glass finishing project engaged five Ceramicx engineers for over a week. “If I had been able to put the problem in front of the Herschel, I could essentially have had the figures immediately,” Wilson explains.

Within its own processes, the machine is enabling Ceramicx to create more energy efficient thermoforming machines for industry.

Another application is in the production of energy efficient ovens for manufacturers of foods such as biscuits, cereals and pizzas. Ceramicx has developed 12 food-industry related patents for Black and Decker, and the Irish company holds the commercial rights for the application of these patents in industrial-scale projects in Europe.

In the case of the Aston Martin BD9, Ceramicx designed and built not only a radiant infrared emitter, but it came up with the best possible solution so that the energy would be adequately absorbed, and the cure would take place in sympathy with the best chemical and mechanical characteristic of the bond. The result is an adhesive bond stronger than a weld, explains Wilson.

Commenting on the impact of Herschel, Cathal’s father, Ceramicx founder and managing director Frank Wilson observes: “For thousands of years, man has played with steel, trying out various heat works to it to make it suitable for certain jobs. In recent years, the plastics industry and other materials sectors have begun to realise that there is a whole range of heat work that can also be applied to improve the performance these materials also.” For these industries, he says, the benefits will be immeasurable.

Commenting on the impact of Herschel, Cathal’s father, Ceramicx founder and managing director Frank Wilson observes: “For thousands of years, man has played with steel, trying out various heat works to it to make it suitable for certain jobs. In recent years, the plastics industry and other materials sectors have begun to realise that there is a whole range of heat work that can also be applied to improve the performance these materials also.” For these industries, he says, the benefits will be immeasurable.